Sound and light in the retina: the promise of a new photoacoustic implant

A team from the Institut de la Vision has validated a new photoacoustic device that uses sound to stimulate retinal cells. This subretinal implant, produced by Axorus, opens up a new avenue for restoring vision in patients with degenerative retinal diseases. The pre-clinical results of this proof of concept were published on 23 December 2025 in Nature Communications.

Degenerative retinal diseases are among the leading causes of vision loss worldwide. They result in a gradual decline in vision, leading to severe visual impairment or even blindness. This deterioration in vision is mainly due to the progressive degeneration of light-sensitive cells called photoreceptors.

Photoreceptors are the gateway to visual information. This information is processed by the retina through various layers of sensory nerve cells: a first layer of photoreceptor cells detects and translates light information into electrochemical signals. The signals are then transmitted, via several layers of cells, to the ganglion cells, which communicate nerve impulses to the brain via the optic nerve. Degenerative diseases generally damage the first layer, leaving the rest of the retinal cells intact. To date, there is no cure for these degenerative conditions. To circumvent the loss of photodetectors, micro-technologies have been developed, including subretinal implants such as the PRIMA photovoltaic implant, which converts light information into electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain.

In this context, Audrey Leong and Thijs Ruikes, a doctoral student and postdoctoral researcher at the Institut de la Vision in Serge Picaud's team, in collaboration with Chen Yang's team at Boston University and the French company Axorus, show that it is also possible to restore the visual information pathway by mechanically stimulating the remaining cells. Using a subretinal photoacoustic implant, they were able to observe in vivo the activation of the visual system in the brains of rodents with defective photoreceptors.

An ultrasonic subretinal implant

In this research, scientists are looking at the active mechanosensitivity of intact cells, which is their ability to turn mechanical stress applied by an ultrasound wave into a biochemical or electrical signal.

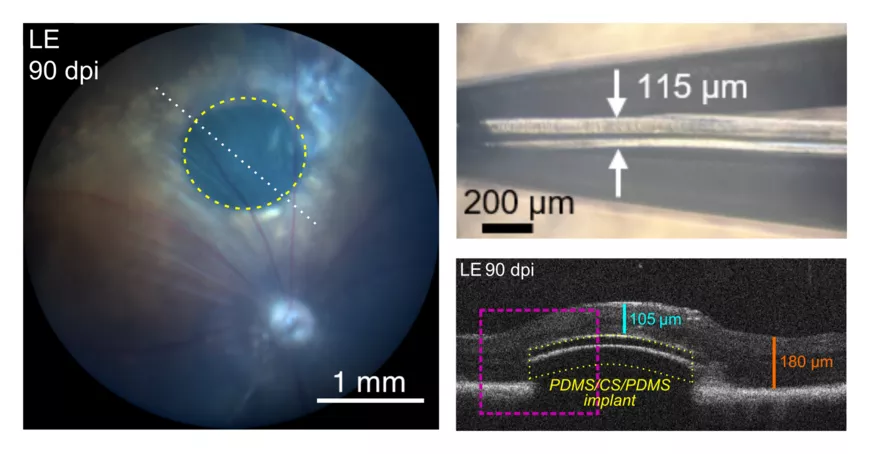

To mechanically stimulate objects as small as nerve cells, they designed a ‘photoacoustic’ transducer: a multilayer film that absorbs a light signal, heats up locally and expands. The thermal expansion generates an acoustic wave that stimulates the retinal cells. Thanks to this device, an ultra-short infrared light pulse (lasting a few billionths of a second) is converted into a very high-frequency acoustic wave (in the order of tens of megahertz). The implant resembles a flexible membrane, no thicker than a fifth of a millimetre, or the thickness of two hairs. By placing the structure in contact with the retina, the researchers observed activity in the ganglion cells located at the implant site and centred on the illuminated area.

The promise of large-scale restoration with high spatial resolution

In addition to being proven in laboratory tests and on experimental models, the system developed at the Institut de la Vision is notable for its potential for high spatial resolution. To significantly restore human vision, the implant should emit with a spatial resolution of less than 0.02 mm and evenly distribute several thousand stimulation points over a total surface area of 25 mm² (the size of a human macula). Until now, none of the implants developed have satisfactorily met these two criteria. For example, the PRIMA photovoltaic implant, currently undergoing clinical trials, although effective, is limited by the size of the photovoltaic microcells and cannot achieve a spatial resolution of less than 0.1 mm. The photoacoustic implant, which is a continuous medium, has no spatial limitation other than the illuminated surface, generating focused ultrasounds with a width comparable to the diameter of this surface. In the study, the stimulation point can reach 0.05 mm in diameter, which already achieves a resolution that is twice as small as the one obtained with PRIMA. Reducing the illuminated area in future studies would bring the spatial resolution closer to the optimal value of 0.02 mm. Furthermore, unlike PRIMA, which is based on a rigid implant with contiguous photovoltaic units, the photoacoustic film has the advantage of being flexible and continuous. It could therefore, in theory, cover a larger surface area than PRIMA (currently 4 mm²), while offering finer spatial resolution.

A pioneering proof of concept

The validation of this subretinal device, developed by Chen Yang's team at Boston University and the French company Axorus, is part of innovative research at the Institut de la Vision into vision restoration, which has notably led to the PRIMA implant. With this proof of concept, researchers are paving the way for the possible use of photoacoustic implants to restore vision in patients with degenerative retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and retinitis pigmentosa. Beyond clinical application, the use of ultrasound raises new fundamental questions, such as: what cellular phenomena are involved in mechanical stimulation? New experimental challenges are also emerging for producing an image with a laser beam. Finally, although the implant meets all biological safety standards, studies still need to be conducted to assess the long-term impact of mechanical stimulation on the retina.

This work illustrates the expertise of the Institut de la Vision in developing technologies at the intersection of neuroscience, physics and biomedical engineering. Unlike existing implants that rely on electrical currents, this approach uses acoustic waves, opening up a completely new avenue for stimulating the retina and, ultimately, restoring vision more precisely over a larger area of the retina.

Scientific publication: Leong, A., Li, Y., Ruikes, T.R. et al. A flexible photoacoustic retinal prosthesis. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67518-6