Brain imaging: a flash in the depths

Seeing the brain in action, neuron by neuron, in real time — this is the ambition shared by many neuroscience teams. Two-photon calcium imaging is currently the gold-standard method for observing and recording the activity of neuronal populations deep within the living brain. However, this approach provides only an indirect — and temporally smoothed — view of neuronal activity.

Valentina Emiliani’s team has now taken a significant step forward, showing that a family of fluorescent sensors long considered unsuitable for two-photon imaging can, in fact, deliver very high-quality signals — provided that the way neurons are illuminated is rethought.

Illuminating neurons to capture the brain’s electrical activity

The brain is made up of billions of neurons that communicate through brief electrical impulses known as action potentials. To understand how perception emerges, how decisions are made, or how disease disrupts these processes, it is no longer sufficient to know where activity occurs — we must also see when and how neurons fire, with millisecond precision.

Directly measuring this electrical signal at its source is precisely what GEVIs — Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators — enable. In the rhodopsin-based sensors studied here, such as Jarvis, a fluorescent protein (the fluorophore) is fused to a microbial rhodopsin embedded in the neuronal membrane.

During depolarization — when the membrane potential shifts from a negative to a more positive state — the rhodopsin undergoes a conformational change. This reduces the efficiency of energy transfer (FRET) toward the rhodopsin, causing the fluorophore to emit more strongly (a positive signal).

The response is nearly instantaneous, on the millisecond scale, and proportional to the voltage change.

JARVIS: a fluorescent sensor designed for two-photon imaging

The research team engineered a new FRET-opsin voltage sensor based on a well-characterized rhodopsin derived from the unicellular green alga Acetabularia. This voltage-sensing domain was coupled to AaFP1, a fluorescent protein among the brightest described to date.

A tailored linker sequence between the two components was finely optimized to maximize the efficiency and voltage sensitivity of energy transfer. The resulting construct was named JARVIS*.

Functionally, JARVIS behaves like a miniature optical indicator embedded in the neuron’s membrane. Its fluorescence intensity changes with each electrical impulse, displaying fast kinetics, strong sensitivity, and high photostability.

Because it is fully genetically encoded, introducing the corresponding gene is sufficient for neurons to produce the sensor themselves — no external dyes are required.

A major challenge for voltage sensors is sustaining extremely high acquisition rates — on the order of kilohertz — since action potentials last only a few milliseconds. JARVIS was specifically designed to meet this demand. Capturing such fast electrical events requires ultra-fast cameras, but within a 1-millisecond window, very few photons are emitted. JARVIS’s high brightness compensates for this constraint, enabling rapid imaging while maintaining clear signals.

Scanless illumination to image neurons in vivo

The second major innovation of this work lies not only in the sensor itself, but in how it is illuminated.

Most two-photon microscopes reconstruct images by scanning a focused laser point across the tissue line by line. Achieving sufficient signal with this approach requires high irradiance at the focal point. The researchers showed, however, that for rhodopsin-based sensors such as JARVIS, excessive light power degrades voltage sensitivity.

The team therefore adopted a different strategy: scanless illumination. Instead of moving point by point, the laser beam is optically shaped to illuminate the entire neuronal soma simultaneously throughout the acquisition period.

This approach fully leverages JARVIS’s properties: baseline fluorescence remains high, voltage sensitivity is preserved, and action potentials emerge sharply — like flashes of light against a dark background — with signal-to-noise ratios three- to six-fold higher than with conventional scanning methods.

These findings demonstrate that combining JARVIS — or similar rhodopsin-based sensors — with adapted illumination strategies enables the transition from studying single neurons to monitoring entire neural circuits, while maintaining high temporal resolution.

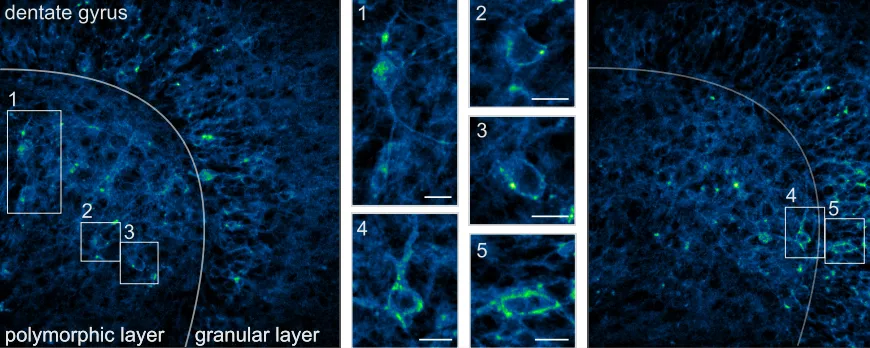

To validate this “new sensor – new optics” pairing under conditions relevant to neuroscience, the researchers tested several sensors — JARVIS, pAce, and Voltron2 — across multiple experimental models: from isolated brain tissue, to zebrafish larvae, and up to the intact brain of awake mice.

This confirms the compatibility of the approach with in vivo imaging under physiological conditions, including in intact cortex.

What this changes for neuroscience research

By demonstrating that rhodopsin-based voltage sensors are fully compatible with two-photon imaging, this study significantly expands the toolbox available for deep brain exploration.

Several implications are particularly promising for research at the Institut de la Vision and beyond:

- the ability to monitor electrical activity of identified neurons with far greater temporal precision than calcium indicators;

- access to fast neural network dynamics critical for understanding sensory coding and brain rhythms;

- the identification of optimal illumination regimes to guide the design of future voltage-imaging microscopes.

For now, this advance remains within the realm of fundamental research. It opens the possibility of studying in vivo phenomena that were previously extremely difficult to capture. By providing a more precise and faithful view of the electrical activity flowing through the brain, it may contribute — in the longer term — to a better understanding of neurological disorders such as epilepsy, neurodegenerative diseases, or visual system pathologies.

It also holds particular relevance for research conducted at the Institut de la Vision. In the retina, most neurons communicate not through action potentials but via graded potentials — continuous electrical variations that are poorly captured by calcium imaging or electrode arrays.

Sensitive, multi-cell voltage imaging could enable direct observation of the analogue computations that transform light detected by the retina into electrical signals transmitted to the brain, opening new avenues for functional studies of retinal circuits.

JARVIS is a playful acronym: * "Just AnotheR Voltage Indicating Sensor”. It reflects the authors’ recognition that many excellent indicators already exist (pAce, Voltron2, ASAP…). A modest name for what is nonetheless a highly powerful tool for neuroscientists — and perhaps also a subtle nod to Iron Man’s high-tech assistant.

Christiane Grimm, Ruth R. Sims, Dimitrii Tanese, Aysha S. Mohamed Lafirdeen, Imane Bendifallah, Chung Yuen Chan, Giulia Faini, Elena Putti, Filippo Del Bene, Eirini Papagiakoumou, Valentina Emiliani - Two-photon voltage imaging with rhodopsin-based sensors - Neuron - February 12, 2026 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2025.12.014